I want to tell you about a new website I’ve made called GIS.tools.

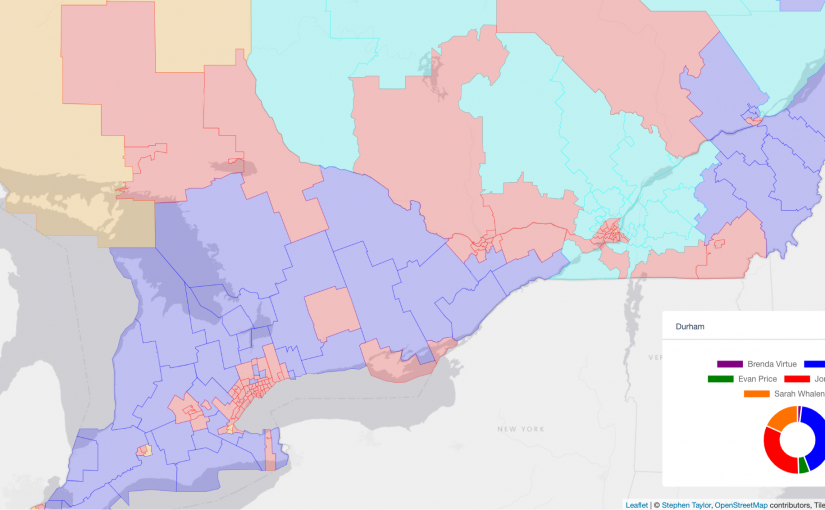

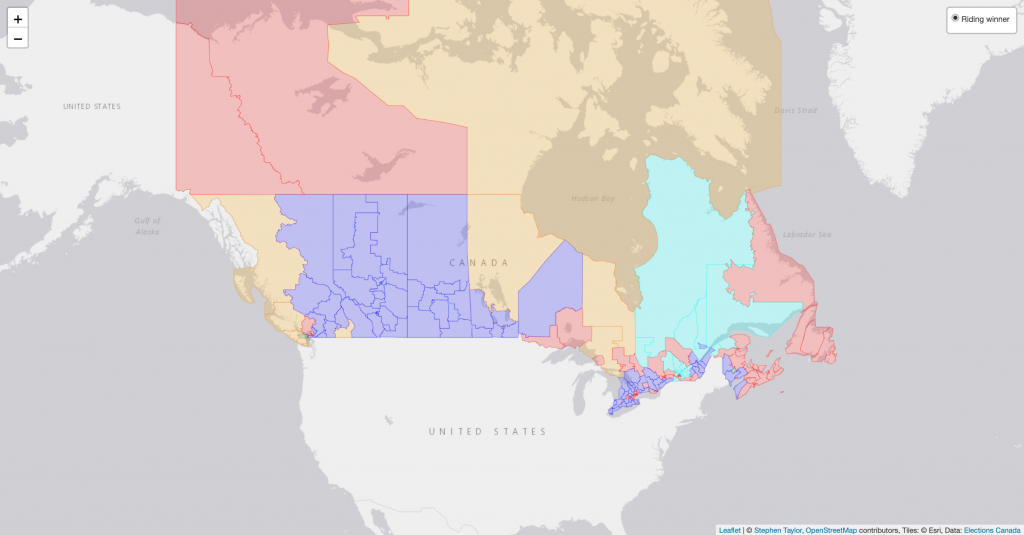

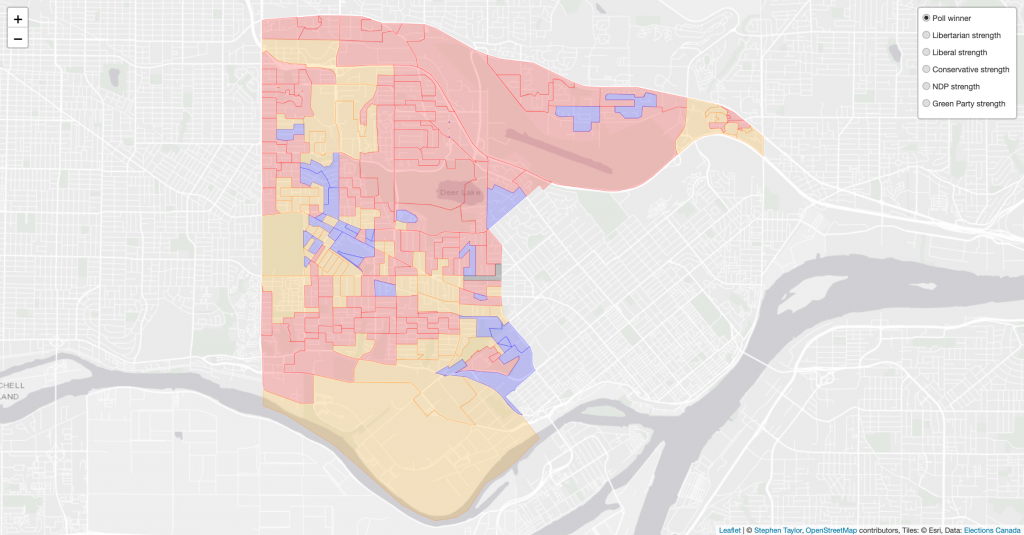

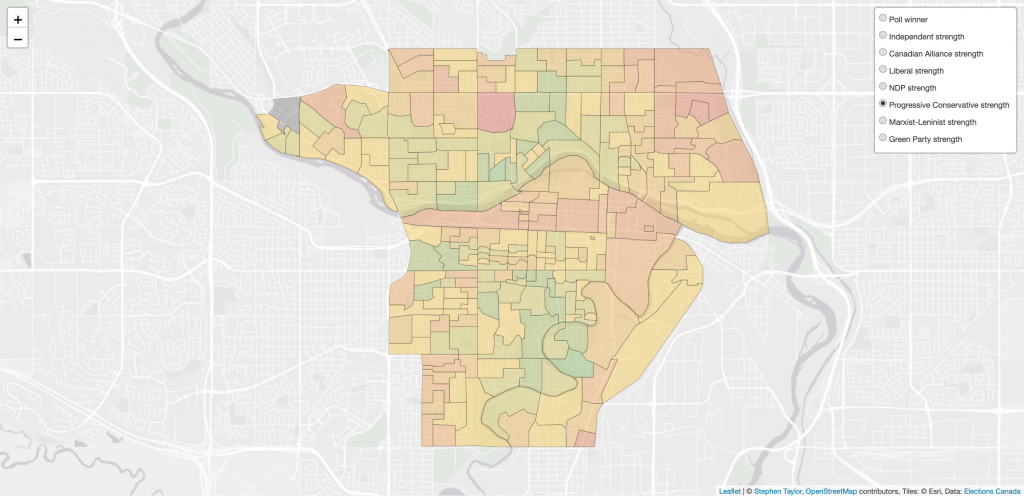

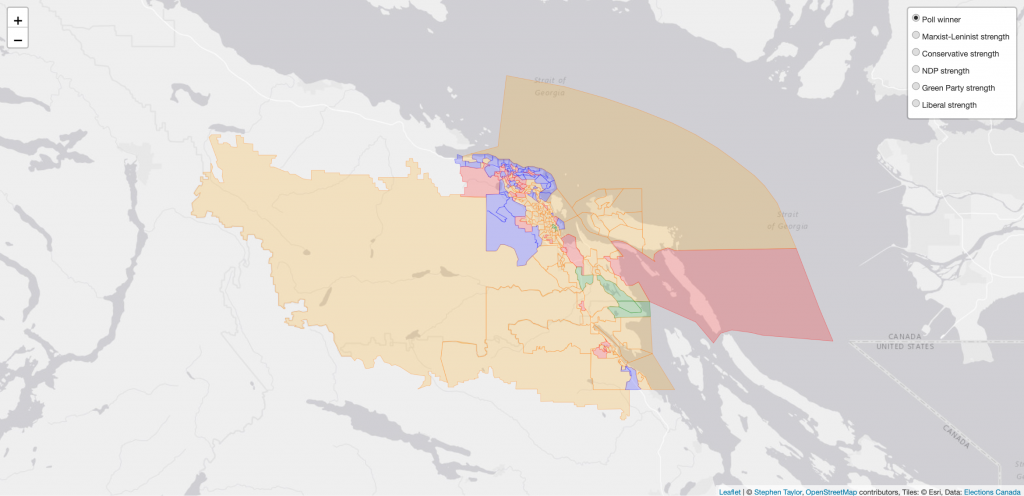

Many of you may know that I enjoy making maps. Online maps. Maps that show us about our world and the data that defines it. I know that puts me in a bit of a rare category of nerdism, but I do enjoy creating them.

My political mapping project continues to gather interest and I often get complimented on it when I go to political conventions. It’s an easy way to find the other political map nerds who travel.

Yes, there’s maybe a couple of dozen of us in Canada – maybe it’s time to start a group chat?

Until then, I continue to scratch the itch and push new frontiers of learning. And that is this project that I’ve been working on with my AI co-workers.

What I’ve built is an extensive online tools website for map makers and I even landed it on GIS.tools.

Yes, that’s the domain name.

I always say the best name for a product is exactly what it is!

For those not in the know, GIS is Geographical Information Systems – the framework for capturing, managing, analyzing, and displaying all types of spatial or location-based data. People who make maps work in the field of GIS.

As you can imagine, there are lot of data in map making, and there’s a lot of file manipulation – often between different file standards from different eras. From Shapefiles, to KML, to GeoJSON – every map nerd has their preference.

Since I never paid for any expensive mapping software, or bothered to learn more than the basics of some of the free products, I’d keep finding myself googling specific online converters, calculators, and raster tools and finding them on a hodgepodge of various websites.

And sometimes the tools just weren’t out there.

So, I’ve been using AI to code these tools and collect them in one place.

I built a Swiss Army knife for map makers.

The result of that effort is GIS.tools.

It has more than 100 GIS tools. From Shapefile to GeoJSON converters, to GeoJSON validators, linters, and fixers, to Hillshade generators, the site probably has what you’re looking for.

And because we live in the current age, I also quite easily translated the website into six different languages. So, French, Spanish, German, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese mapmakers aren’t left out either.

So whether you need an EPSG Reprojector, a CRS Metadata Inspector, an MBTiles validator, or a Heatmap renderer, or are just learning about the tools of the trade, please do check out the site.

Most tools even have example data so you can get an idea of what they do!

You’re probably a fellow map nerd if you’ve read this far. And knowing my people, you probably have a website too. If you appreciate this sort of thing being out in the world for free, I’d appreciate a link so that others can discover it too!